There are few short stories more famous (or more memeable, thanks to the BTS music video “Spring Day”) than “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas” by Ursula K. Le Guin. In it Le Guin lures the reader into co-creating the wondrous world of Omelas, a utopia that even the narrator admits seems unbelievable—until one takes a look at the cost of creating and maintaining this magical realm. “Their happiness, the beauty of their city, the tenderness of their friendships, the health of their children, the wisdom of their scholars, the skill of their makers, even the abundance of their harvest and the kindly weathers of their skies, depend wholly on… [the] abominable misery” of a single child, sacrificed and imprisoned somewhere below the city. The question then stands: do you, the reader, accept this bargain, or do you walk away from it? Can you imagine another land, perhaps even a better land, without this bargain?

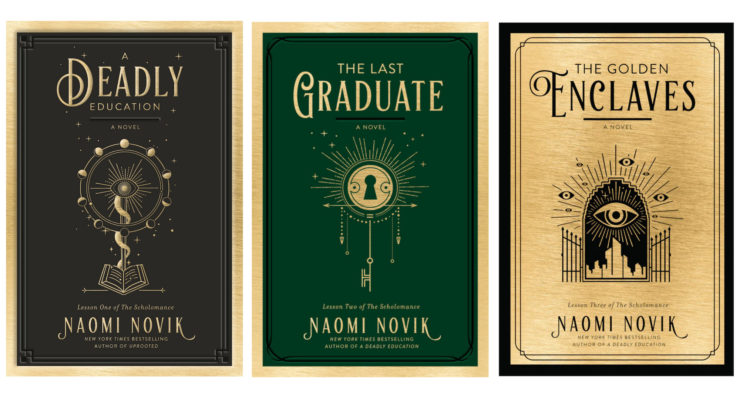

Le Guin posits, in her acceptance speech to the 2014 National Book Foundation’s medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, that this is the central task of contemporary writers and artists, to envision these kinds of worlds free of capitalism. “We live in capitalism,” she said. “Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings… power can be resisted and changed by human beings; resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art—the art of words.” One famous response to both this call to action and Le Guin’s most famous short story comes from the always brilliant N.K. Jemisin, who asks her readers, point-blank, if they can envision a utopia without secret evil in “The Ones Who Stay and Fight” (originally published in How Long ’til Black Future Month? 2018). One more unexpected, but much longer response comes from Naomi Novik, in her Scholomance trilogy. Though outwardly the series is a young adult fantasy set in a dark and dangerous magical boarding school where “most of the time less than a quarter of the class makes it all the way through graduation,” Novik builds the literal foundations of her fantasy world on “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” and then spends the series slowly building up to the destruction of this foundation, and the construction of something new and better in its place (A Deadly Education 9).

Before I dig into the anti-capitalist message of the Scholomance series, I should issue a warning that these books have received some backlash. In its focus on the perils of capitalism, race is not always treated as thoughtfully and delicately as it should be. Larissa Irankunda, in a 2020 article for The Mary Sue, points out a number of missteps Novik made the first book of the series, including a negative passage about locs (for which Novik has apologized on Twitter) and reader dislike of the way the racial backgrounds of Novik’s POC characters, particularly half-Indian, half-Welsh protagonist El, are portrayed in text. The complex issue of biracial representation is not an unusual one for Novik to well-meaningly fumble—I myself have written about the mixed results of Novik’s attempts to understand and empathetically portray the perspective of a previous mixed race character in her Temeraire series—and this Book Riot article by Namera Tanjeem investigates the implications of El’s lack of connection to her Indian relatives more in-depth, and discusses how this can, in fact, be a realistic scenario for many mixed race people. There is also some debate over the term ‘mana,’ which could come either from RPGs and Magic: The Gathering, or from Polynesan tradition. I personally found these issues to be well-meaning missteps but I am not the ultimate judge on these things, and your mileage may vary. I also issue another warning to you, Tor.com reader: from here on out, there will be spoilers for the entire series.

Like “Omelas,” the Scholomance series is written in the first person, but as less of a co-creative imaginative exercise and more of a defensive confessional from the perpetually angry, snarky protagonist Galadriel “El” Higgins. El wants the reader to understand how limited her choices are—and yet, she is always finding alternatives to the evil her circumstances encourage her to embrace. To better understand this alternate path offered by El later in the series, and to understand how the Scholomance series responds to “Omelas,” we must first look at Le Guin’s statement from said short story that “the treason of the artist” is partly “a refusal to admit the banality of evil.” That recognition of the banality of evil forms the core of Novik’s magical system. In the first book, A Deadly Education, El explains that all spells must be powered by “life force or arcane energy or pixie dust or whatever you want to call it; mana’s just the current trend” (8). There are two ways to gather up this force: by your own exertions, like El’s go-tos of crochet or push-ups, which makes it mana, or by yanking it from “things complicated enough to have feelings about it and resist you,” which taints the power, and turns it into malia (8). While El herself points out that malia turns the person who uses it into a maleficer who sometimes can only use malia thereafter, and who will eventually die from using such tainted magic if they don’t abstain from magic entirely for years (11), it is still a common method of powering spells. There are at least two maleficers in El’s year at school, and El points out that being a maleficer is a legitimate way to survive your school years, as the Scholomance “almost never kills” them (9). What is essentially a scholar turning into a serial killer becomes sound strategy in the Darwinian world of the Scholomance, a miserable magical boarding school where young wizards try to survive to adulthood by hiding within its walls from maleficaria, or mals: evil monsters that are generated by any use of malia and which feed on mana (The Golden Enclaves 173). Mals are particularly fond of pulling said mana from young and defenseless wizard children. As easy as it is for mals to break into the school and eat you, being in the Scholomance increases your chances of survival from one in twenty to one in four, so anyone offered a place at the Scholomance takes it. This, too, comes at the price of banal evil.

As El explains:

we have to pay for that protection. We pay with our work, and we pay with our misery and our terror, which all build the mana that fuels the school. And we pay, most of all, with the ones who don’t make it. (A Deadly Education 19)

This last line in particular seems like an allusion to the title, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” and illustrates how the banality of evil means not merely learning to live with constant misery and terror but accepting that your unhappy survival depends on the greater misery and terror of those even less fortunate than yourself. This, like the maleficer route, is an accepted and acceptable bargain in this magical world—and why? Because if you do make it, you have a chance of joining an enclave. An enclave is a magical structure tethered to the real world via a magical foundation, where wizards are relatively safe from mals and where they can build fantastical worlds full of incredible beauty luxury. The fairy-tale-esque secret garden of the London enclave, the shining Gilded Age train station of New York, and the modernized scholar’s paradise of Beijing allow those that live within them to be safe, and above all, to be happy.

In the final book of the series, The Golden Enclaves, Novik makes it even more explicit that Omelas is at the heart of her world-building. When the Beijing enclave is near collapse, and El’s friend Liu makes a desperate effort to inform El and company that the solution to this problem threatens her life, El and her friends stage a rescue mission. They find Liu not in the wonderful, magical, fantastical part of the Beijing enclave, but in a small room underground: trapped in a circular magic container with powerful wizards piling bricks of mana on top of her in a manner reminiscent of the stones piled on top of Giles Corey during the Salem Witch trials. This process will create a new magical foundation for the enclave, but it will also transform Liu into a maw-mouth, one of the most dangerous and voracious of mals: a monster of endless and limitless consumption, who extracts all the mana out of its victims by swallowing them whole, and then keeps generating more mana by keeping its victims alive and suffering eternally within itself. El is the only person to have ever completely killed a maw-mouth, and she only managed to do this by also killing every single one the victims trapped within it. The maw-mouth’s endless mana production, a horrified El realizes, is the only way wizards have created enough magical power to build and expand their enclaves.

By sacrificing Liu, by crushing her into monstrousness, these wizards are building a paradise on top of “torture, and pain, and betrayal,” (The Golden Enclaves 273) and one child’s abominable misery. This is not only a world literally built on Omelas, but a brilliant metaphor for capitalism. Growth and luxury stem from exploitation and unchecked consumption. Capitalism becomes a self-perpetuating monster, one that destroys the vulnerable to ensure the privileged live in ever-increasing, ever-expanding comfort and security. When capitalism is left unchecked, it will consume even the privileged. But for those on top, this bargain holding up their societies is invisible, and the collapse of the world seems unimaginable. Those on top refuse to acknowledge that those on the bottom of the social ladder are “being endlessly tortured to death so someone else could live in luxury on their graves” (338). Later in the book, El discovers there are also colonial ties to this kind of unlimited expansion. The head of the Shanghai enclave reveals that more powerful enclaves send their maw-mouths to far away countries too weak to build enclaves themselves, or to defend themselves. London, for example, sent all their maw-mouths to India during World War II (376).

But El, like those who walk away, refuses to accept this bargain. With the help of her friends and Liu’s family, El removes Liu from the machine. El decides not to destroy the enclave in revenge for what they did to her friend, but to offer it a different way forward. Instead of using those magical bricks to crush a child of Omelas into a maw-mouth whose consumption of other wizards would pour mana back into the foundation of the enclave, El uses the mana bricks as the foundation itself. It is a risky endeavor. El has spent most of the series first searching for, and then learning magic spells to create golden stone enclaves—enclaves built on mana, not malia—but she has never cast the spells herself, and it is difficult even for her to lift even a single brick of compressed magic on her own. And there are major drawbacks for the enclaves. Without the maw-mouth to supply endless power, there is a set amount of magical power undergirding the enclaves. Enclaves cannot grow at the rate they did before and their members will have to make even tougher choices about how to use their limited resources and who should be invited to enjoy them. However, when faced with a choice between existence without the same rate of expansion, and the total annihilation of their enclave, everyone takes El’s bargain. More than that, they begin to help her. El and Liu’s classmates from the Scholomance see El struggling to lift the bricks and begin doubling up to pass them to her. Then, the entire enclave joins in. They tear down the walls hiding the shameful sacrifice at the heart of their society and replace it with something better: a new, collectively built foundation of sheer will, belief, and magic. They beg of these raw materials: “stay here, please stay, be our shelter, be our home, be loved.” (292) This works. The Beijing enclave is saved, without having to turn Liu into a maw-mouth. Stopping the exploitative misery of Omelas—of capitalism—comes from, as El puts it, giving “ordinary, mostly decent people, the ones who hadn’t been able to watch, another way” (304).

The second time El offers this new way—once again in service of her friends, this time a boy named Ibrahim, in Dubai—this alternate path becomes a more clearly delineated, pragmatic path forward. Anyone who willingly offers even a mana pebble (not just a mana brick), can be part of this new society. El watches as the walls surrounding the old maw-mouth foundation are torn down, and everyone uses a magical oven to create “a single flat stone, all of them in different colors, some smaller and some larger, polished and rough” made of their own magical energy (316). She also insists on “an absurdly low price for an enclave place,” so that “almost any wizard” could pull together enough mana if they are willing to take El’s bargain (317). Babies with “pea sized pebbles” contribute as much as long-standing council leaders, and every single person places their stones together, smashing the old, rotten foundation and creating a new one—stones from each according to his ability (318). In return, all who took the bargain will be safe.

This kind of enclave building requires lowering the barrier of entry, personal sacrifice, and a degree of coordinated, collaborative action that is difficult to organize even when a community is staring down destruction. As the head of the Shanghai enclave characterizes it, the twentieth and twenty-first century creation of so many new enclaves and the expansion of old ones was “building our own destruction together” (176). The Cold War-esque mutually assured destruction that has been the norm until El’s new enclave building results in the head of the New York enclave trying to create a superweapon: her son, Orion. Orion is a maw-mouth in human form, the most efficient mal hunter the world has ever seen because he is the most dangerous mal in the world. He consumed the maw-mouth that had been created to build the Scholomance and, in effect, became the foundation and source of mana for the school. He, like Liu, is the child of Omelas, never given a choice in his sacrifice, but still desperately trying to make it meaningful and to allow the people for whom he has been sacrificed to survive. Orion suffers so greatly from this terrible self-knowledge that he asks El to destroy him, as she has destroyed other maw-mouths. El can only kill maw-mouths by telling all the people inside it that they are already dead. But, crucially—she now only destroys maw-mouths when she can build something else better in its place. She tells Orion he is already dead, but asks him to stay anyway, and fulfill “the beautiful lie that the Scholomance had been built upon,” to “shelter all the wise-gifted children of the world.” (392). Her own power isn’t enough for this, but her friends, including Liu, begin to pour their mana into her spell. Then everyone else assembled, from Orion’s parents to the head of the Shanghai enclave, pour all their longing for safety and all their ability to make their wishes into reality into the spell. They transform Orion from a sacrifice who knows mostly hunger and horror to a valued member of the community; someone who chooses to stay a part of his society as a protector instead of merely surviving within it as a monster. He becomes the cornerstone of a new Scholomance, one that can offer a better, fairer chance of survival to the next generation. (He even institutes a summer break (409) so that the children get a break, and he and El can go monster hunting together.)

This is at the heart of Novik’s imaginative future; this is her response to Le Guin’s call to action. We live in a world like that of the Scholomance series, where certain societies are safe because they have built their success on the sacrifice of others: the vulnerable, the colonized, the weak. But this is a very shaky foundation. The greed upon which society grows will ultimately consume it, particularly if, as in The Golden Enclaves, the powerful only agree to find a new way forward when it becomes “a matter of immediate self-preservation” (398). There is a timely practicality to this warning, in a quasi-post pandemic world where ecological disaster looms, and the flaws inherent in the capitalist system have become too blatant to ignore. If you do not make some sacrifices now, if you do not learn to live with less, to share with others, and to face the exploitative foundation of your privilege and replace it with something better: not merely your entire way of life, but your entire existence is in peril. Those who walk away from Omelas know that a city of happiness cannot stand upon exploitation of the weak. They know it must be built from the willing sacrifice of everyone in it, and they are willing to put in the work to ensure everyone knows this and agrees to it. Those who walk away from Omelas know that if each gives according to their abilities, all will receive according to their needs.

Elyse Martin is a Chinese-American Smith College graduate who lives in Washington, DC with her husband and two cats. She writes reviews for Publishers Weekly, and her essays, articles, interviews, and humor pieces have appeared in Slate, The Toast, Electric Literature, Perspectives on History, The Bias, Entropy Magazine, Publishers Weekly, Smithsonian Magazine, and Tor.com. Her article, “Please Let Women Be Villains,” was listed as one of the “Notable Essays and Literary Fiction of 2021” in Alexander Chee’s The Best American Essays 2022. Her debut graphic novel, Copy Cat, with illustrator Sean Rubin, will be published by HarperAlley in the autumn of 2024. She spends most of her time writing and making atrocious puns—sometimes simultaneously.